Software is often designed around modeling things in real life. The problem is, these designs do not translate well to clean software. The resulting architecture and code base are often coupled and difficult to maintain. A good example of coupling is interacting with a rails application with the intent of creating a new user record and accidentally triggering a welcome email to be sent. In this example, persistence is tightly coupled with domain logic. These tightly coupled applications violate one of the most important principles in software architecture, the single responsibility principle.

Single Responsibility Principle

The single responsibility principle can be defined in two ways:

- An object should do only one thing.

- An object should have only one reason to change.

The basics and understanding are simple; however, implementation is considerably more difficult. Drawing the dividing line through an object’s responsibilities can be difficult, and it is possible to split an object too many times.

There are also a few more things to keep in mind during when thinking about single responsibility. How often are things changing inside of the class, and how would I describe the object’s purpose to someone without any knowledge? When a class has pieces that are changing at different rates, the single responsibility principle is being probably being violated. Also, if you describe the object and use the words “and” or “or,” the class might be violating single responsibility.

Code Smells

There are also a number of code smells that can be indicators of single responsibility violation:

- Methods that are too long. (Fewer than 5 lines is often a good number to aim for.)

- Sawtooth code, which has many alternating levels of deep indentation.

- Large values of cyclomatic complexity, which is a measure of how much decision logic is contained in a function.

As always, these principles are open to interpretation and should be applied pragmatically.

Problem: Single Responsibility in Traditional 3-Layer Architecture

In a traditional 3-layered architecture, we split things into a presentation tier, a logic tier, and a data tier. This solves a few problems with single responsibilities, but it also creates a few, most prevalently within model–view–controller (MVC) projects with a complicated domain.

In a traditional 3-layered architecture, we split things into a presentation tier, a logic tier, and a data tier. This solves a few problems with single responsibilities, but it also creates a few, most prevalently within model–view–controller (MVC) projects with a complicated domain.

In MVC, views are kept logic-less and controllers are kept thin. Domain logic ends up getting shoveled into the data tier, resulting in objects that are a tangled mess of persistence and domain logic. The problem is that the SRP is not well represented in 3-layer architectures. We need a different way of looking at our software which promotes single responsibilities and decoupling.

Solution: Ports and Adapters

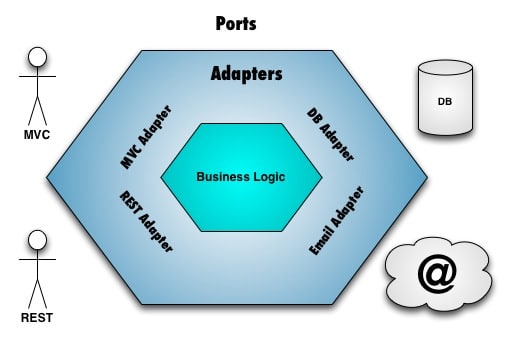

Ports and adapters, also known as hexagonal architecture, is an attempt to solve this problem of business logic becoming tightly coupled to other dependencies such as client frameworks and persistence. When implemented well, ports and adapters results in little classes with well-defined pieces of functionality. With these pieces of well-defined functionality, the classes are easy to name and the code base becomes comfortable for developers, resulting in reduced cost of maintenance and development. In addition, individual pieces can be mocked out, developed, and tested in isolation. Domain logic can be isolated from side-effect-inducing dependencies, specifically databases and web services.

Visualization

Ports and adapters presents a new way to view interactions between your objects, from a domain perspective. It can be visualized as an onion diagram, with the external entities on the outer most layer, adapters on the inner layer, and the domain logic at the core. I generally try to place the event-driving dependencies on the left and cooperative dependencies on the right.

Ports

On the outermost layer lie the ports. These are pieces of dependent code or services that we do not have control over. These ports are anything external to our business logic such as user clients, persistence, and communication frameworks. I tend to split these up into two categories, event generating and collaborative.

The event-generating dependencies are ones that generate the events which drive our business logic. Our business logic will eventually be called on from these requests and eventually play a role in the formulation of a response. These can be any number of things such as users interacting with an MVC framework, other programs making calls against a web service, a developer manipulating objects in a REPL, subscribing to a message queue, and even automated tests.

The collaborative dependencies assist the domain with accomplishing a specific task. Examples of collaborative dependencies are databases, ORMs, external web APIs, and the producing side of a message queue.

Adapters

In the middle layer lies adapters, a gang of four pattern also called a wrapper. The adapter’s job is to translate an interface from a framework or class into a compatible interface. In my opinion, this is the most critical piece of ports and adapters. It provides an anti-corruption layer and keeps the external dependencies from leaking into our domain logic. By keeping these external dependencies from leaking, dependencies can be quickly interchanged, as long as the same interface is kept. This results in the code base becoming agile and flexible.

If a persistence framework were to be changed, there are only a handful of objects that will need to change — compared to a leaky codebase, which will require touching almost all pieces of code. The fewer objects we have to change, the less chance that something will break and the less costly maintenance and development becomes. Repository objects, which wrap an ORM, usually reside at this layer. There is also an added benefit: if table access becomes slow, it is easy to look in one place and see all the queries that are being used, which can make tuning and performance analysis easier.

The adapters for event generating dependencies are a little bit different since the users of our application reside at the port layer. Adapters are the implementation of MVC views, MVC controllers, and REST interfaces. These adapters will call through to the core domain to trigger specific actions.

For more information about ports and adapters, I recommend reading Alistair Cockburn’s article on hexagonal architecture, as well as Growing Object-Oriented Software Guided by Tests.

Thanks for your insight Tony, I think you’re right on the money when it comes to how MVC apps evolve. Inititially it can be quick and simple to stuff app logic into Models, but without keeping SRP in mind, the Model layer can get really hairy really quickly.

Along these lines, I’d like to recommend Jeffrey Palermo’s article series (4 parts) on Onion Architecture:

The Onion Architecture : part 1

In it he describes exactly this sort of system – pushing external dependencies out to the edges of your codebased, and keeping the application logic at the core, using adapters to connect the core to the edges. We’ve started building systems with this in mind and have had much more success keeping things decoupled and resilient to change – especially change we can’t control (i.e. integration service contracts changing with little notice) than in the traditional 3-tier model.