Article summary

Let’s say you’re creating a feature branch off a master for a new feature you are about to implement. You finish up your work on the feature branch while one of your colleagues is making some changes on the master branch. Before creating a pull request, you might want to make sure you have the most updated master on your feature branch. There are a couple of ways to do this: Git merging and Git rebasing.

Git Merging

What it is

I think of a merge as saying, “Git, please cram all of my new stuff into the existing stuff. If you cannot figure out how to cram it all together, ask me to resolve the conflicts.”

How it works

Say that Lydia creates an empty repo with a text file. She adds, “Hello World.” to the file and commits the change as C1. Lydia then realizes that she should have added more to this file, so she adds, “This is a sentence.” as the second commit (C2).

HelloWorld.text now looks like this:

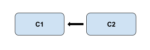

And the commit tree looks like this:

Then, Lydia decides she wants to add even more sentences to HelloWorld.txt, so she creates a branch. Let’s call the branch feature/more-sentences. She adds the sentence, “Another sentence.” to the HelloWorld.text file and commits that change as C3.

As this is happening, another developer decides that “This is a sentence” should become “This is a sentence.” She commits this change to master as C4.

On master, HelloWorld.txt looks like this:

On feature/more-sentences, HelloWorld.txt looks like this:

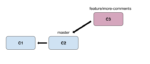

To get the updates on master into her feature branch, Lydia could merge master into feature/more-sentences. The last commit on master (C4) is not an ancestor of the last commits on the branch feature/more-sentences (C3), meaning that there have been additional commits on master since the feature branch was created.

To resolve the new commits on master with the feature branch, Git does a three-way merge between the tips of the two branches (C4 for master and C3 for feature/more-sentences) and the last common ancestor of those two branches (C2). The three-way merge creates a new commit with C3 and C4 as its parents.

HelloWorld.txt now looks like this:

Tradeoffs

Merging does not re-write Git history. If you want to keep an accurate representation of your repository without losing any history, merging might be the way to go.

However, a historic Git history might mean compromising a clean Git history. Using merging as the primary means of integration might mean more work-in-progresss commits and merge commits.

Git Rebasing

What it is

Rebasing is similar to asking Git, “Can you just add my new stuff on top of the stuff that has already been done?”

How it works

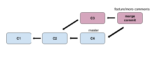

Let’s go back to the previous scenario: Lydia created the branch feature/more-sentences off the master. In the meantime, another developer had been adding commits to master. It looked like this:

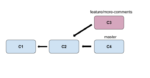

If Lydia wanted to get the updates from master into her current branch without doing a merge commit, she could rebase her current branch on master (Git rebase master). Rebasing off of master would replay all feature branch commits onto the tip of master.

Because the commits on the feature/more-sentences branch are stored in a temporary file and replayed onto master, Lydia will essentially re-write her Git history with new commits. If there were any conflicts when replaying the commits on to the tip of master, Lydia would get to decide how to resolve them for the new commit being created.

Tradeoffs

Rebasing on a public branch can cause confusion. This method changes history by creating entirely new commits. If you rebase and push the changes to the remote, the remote might have a different history than someone else’s local copy of the same branch (if they have not yet fetched). The deviated history could lead to chaos if a developer pushes commits from their local branch to the rebased remote branch. So if you ever rebase a public branch, it is important to communicate that to the rest of the team.

If rebasing is used carefully, it can give you a lot of flexibility. You can do things like create a Feature Branch A off of Feature Branch B, and then move the commits on Branch B (but not Branch A) over to master. For more on rebasing branches off of other branches, you can check out my colleague’s article on Git gardening.

Rebasing also allows you to clean up unnecessary or poorly worded commits. When rebasing one branch onto another, you can rename commits, combine commits, or entirely delete commits. This helps you maintain a cleaner Git history and makes it easier to find a commit when performing something like a Git bisect.

My personal favorite is that you no longer have merge commits in your Git history. When I am looking through Git history to find a specific change, I am concerned with figuring out distinct steps to create the feature, not with understanding the ins and outs of the implementation history. Though merge commits might show how the features were implemented and merged in, they don’t concisely sum up a chunk of work.

Excellent post. This topic seems so complicated to me (a lone wolf developer who now is working with a team). Thanks.

Excellent description (ELI5!). In section “Git Rebasing”, subsection “How it works”, the first figure in this subsection seems incorrect. I think the intended figure is the one that has four commits, not three–i.e., C1, C2, C3, and C4 where C3 is another developer’s commit to the Master branch. (P.S. Please number your figures–e.g., Fig. 1, Fig. 2, etc.–so that others can reference specific figures by number. Thanks…) Feel free to delete (or not publish) this comment as you see fit.