Article summary

- Backstory!

- Send Only App Traffic over the VPN (Without a VM)

- Hooking Up Simulators and Emulators to the VPN

- A Weird Diversion into Awkward Interface Design

- Building Your Own “Automatic” Proxy Configuration

- All the Things that Can Go Wrong with a PAC File

- Serving it Up

- What Were We Building Again?

- A Weird and Wonderful Setup

What do you do when you need to use a VPN to develop your app but you also need Zoom to stay connected to your team via video chat? If you’re like a lot of developers, you connect to the network and just put up with laggy audio and video.

But what if you didn’t have to? What if you could use the VPN to develop your app, without slowing down your whole network? Sounds great, right? A while ago, we set that up for folks who work on websites. Here’s how to make it work for your in-development mobile app across all manner of simulators, emulators, and physical devices.

Backstory!

I’ve been working on a mobile app that, like a lot of apps, connects to an API. It hasn’t been through a security audit yet, so exposing the API on the public internet is probably not a great idea. But I’m working remotely, and I need to work with the API before that audit is finished. What to do?

Use a VPN! The network that hosts the API uses a Cisco AnyConnect VPN, and there’s a Cisco client for macOS. So when working on the app, I launch the client app and get access to the API as though I’m on site. It’s great!

Except I’m also on Zoom calls (a lot), and the VPN server is a bit under-provisioned for the amount of traffic that it’s been handling lately, so my calls lag pretty badly. The resolution drops. The sound cuts in and out. It’s… less than great.

Fortunately, networks are malleable. If you know the right commands and have the right open-source tools, you can set up a selective connection to the VPN. This way, my API calls go over the private network, but my Zoom calls go over the (much faster) regular internet.

Send Only App Traffic over the VPN (Without a VM)

With a little bit of shell scripting, you can combine openconnect (a configurable VPN client) and ocproxy (a SOCKS proxy server) into a tiny executable that lives in the main repo with your source code. It’ll look something like this:

# start-vpn

#!/usr/bin/env bash

# Starts an OpenConnect VPN client and an OCProxy

# SOCKS5 proxy so that we can send API traffic through

# the VPN without also forcing Zoom traffic through it

PROJECT_PROXY_PORT=8089

openconnect \

--script-tun \

--script "ocproxy --dynfw $PROJECT_PROXY_PORT --allow-remote" \

"$PROJECT_VPN_ENDPOINT"

With that in your repo, any time you need to access the API, you can run start-vpn to open a connection to the VPN. Crucially, instead of taking over your entire network, it just exposes a SOCKS5 proxy on port $PROJECT_PROXY_PORT and forwards traffic on that port through the VPN.

Most development tools are built to work with proxies. If you need to run query an API with curl, for instance, you can run ALL_PROXY="socks5h://localhost:$PROJECT_PROXY_PORT" curl https://api.server/endpoint-i-care-about to route that request through the VPN. More realistically, you can write a little wrapper script like vpn-curl, which sets that environment variable for you.

Hooking Up Simulators and Emulators to the VPN

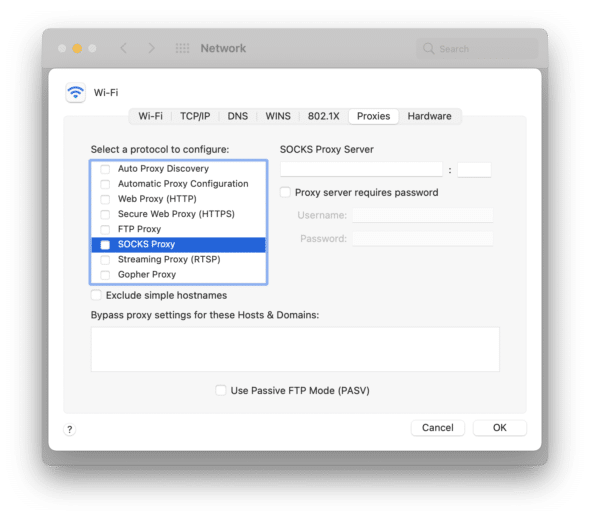

Some dev tools, notably iOS simulators, don’t have independent proxy controls. Instead, they inherit proxy configuration from the operating system. No big deal, right? We can just use the network configuration panel in macOS to add a simple network rule that sends development API traffic over the proxy, while leaving Zoom traffic untouched. Operating systems have had proxy configs for decades, so surely that’s a solved problem with a nice interface, right?

Hmm… nothing here. I guess we could set it up so that everything goes over the proxy, and then write a whole bunch of rules for things that shouldn’t, like Zoom. But I don’t know what domains Zoom uses, and maintaining a whole list of rules for Microsoft Teams, Google Meet, etc. seems like a pain. We know the domain that we want to send over the VPN. How can we do that?

A Weird Diversion into Awkward Interface Design

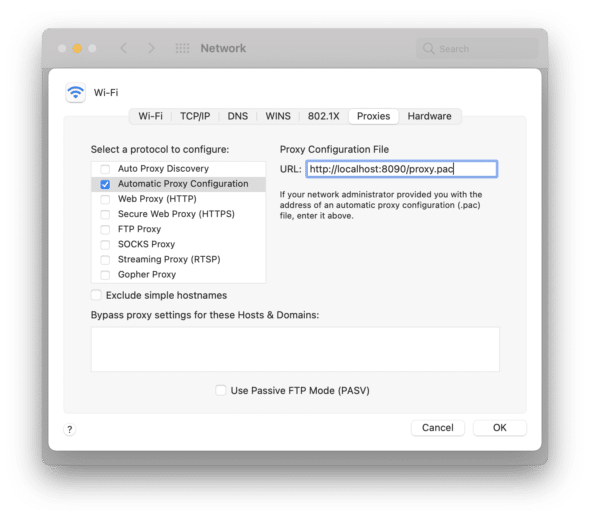

Turns out, if you want to send all of your traffic through a proxy, there’s a simple, intuitive UI for setting that up. If you want to send almost all of your traffic over the VPN, there’s a mostly intuitive UI for that too. But if you want to send only some of your traffic over a VPN, you have to run a web server and write some JavaScript.

Yup. JavaScript. 🥳

To make this work, I got to learn all about PAC, a file format that vends a single JavaScript function that an operating system like macOS can use to determine whether an incoming request should travel over a proxy or go directly to the internet. Here’s how it works.

Building Your Own “Automatic” Proxy Configuration

First, we’ll configure the network to use Automatic Proxy Configuration (it may be named a little bit differently in your OS). Fill in this network settings panel with a local URL on a predefined port — not the $PROJECT_PROXY_PORT from earlier. We’ll use that later.

Then write a single JavaScript function named FindProxyForURL. According to MDN’s docs, the name matters.

// proxy.pac

function FindProxyForURL(url, host) {

var proxy = "SOCKS5 localhost:8089; SOCKS localhost:8089; DIRECT";

if (

host.includes("api-server.dev") ||

host.includes("ipinfo.io")

) {

return proxy;

}

return "DIRECT";

}This tiny, straightforward script is the result of a lot of trial and error. It basically says that, for a given packet, if the destination URL includes either api-server.dev or ipinfo.io, then send it through the proxy. Otherwise, send it over the regular network.

The rough idea of how PAC files work is really well documented on MDN, but the specifics of how each OS uses it are invisible, undocumented, and (as far as I can tell) known only by the developers that implemented this feature.

All the Things that Can Go Wrong with a PAC File

Take, for instance, that variable proxy. It tells the OS that traffic should go through a SOCKS version 5 proxy at localhost on port 8089. If that fails, try connecting to a SOCKS (version ambiguous) proxy on the same port. If that fails, just send the bits directly to the internet without any proxy.

Now, that variable explicitely needs to be a var; don’t try bringing your fancy let and const syntax around to play. And it needs to be defined inside FindProxyForURL. Any lines outside of that function will not be executed. This was documented nowhere.

The weird double definition of the proxy URL is necessary because some tools need to know that they’re connecting to a SOCKS version 5 proxy. They’ll fail silently if you only provide the SOCKS … string. Other tools will assume that you meant SOCKS version 5 and get very offended if you try to specify. They’ll happily connect to a version 5 proxy, but they’ll ignore the SOCKS5 … string altogether.

I included the DIRECT postfix to try to make behavior consistent across all systems. Some browsers, notably Firefox, will drop packets if they can’t connect to any proxy in the cascade (unless you have that postfix). Other systems, notably macOS and Safari, will fall back to sending your traffic over the regular network.

All of this was made infinitely harder to diagnose because there is no way (that I could find) to get an error message from the subsystem that parses and executes PAC files. All you can do is try it and see what happens.

Serving it Up

You might think that you could specify a local file for PAC. It’s a weird JavaScript function in your system settings, but surely you can just drag and drop that file onto the Settings app, right? No. Thou shalt serve it over HTTP with a very specific mime type (application/x-ns-proxy-autoconfig, if you’re curious). So that’s… odd.

But not to fear. There are a ton of really good tiny web servers available. Pick one that you like. I use miniserve, an app with a good CLI, written in Rust, that serves files or directories with no fuss. It even guesses the right mime type for a PAC file. Seriously, Rust community, you made my day with that one ❤️.

You’ll need this server to be running any time you want to use the VPN, so take a moment to make that easy by wrapping your server up in a script that looks something like this:

# start-pac-server

#!/usr/bin/env bash

# Serves a Proxy Auto-Config file so that you can configure

# macOS, iOS, and Android devices to send project traffic

# through the VPN without forcing every device to have its

# own independent VPN connection.

PROJECT_PAC_SERVER_PORT=8090

miniserve extras/proxy-auto-config-server \

--port "$PROJECT_PAC_SERVER_PORT"

What Were We Building Again?

Enough with the diversions — let’s bring this thing home. With these two shell scripts and the PAC file, we have a proxy setup that works for all tools, including iOS Simulators, Android Emulators, curl, Insomnia, and the rest.

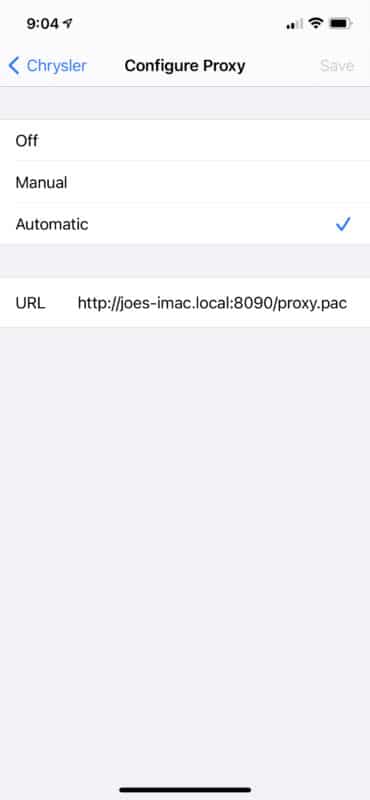

As an added bonus, whenever you want to test the app on a real phone, you can use that same proxy config (thanks to the --allow-remote option of ocproxy). Just tweak your PAC file to use your computer’s hostname instead of localhost, and configure your phone to connect to the PAC server that’s running there. It should look something like this on an iPhone (Android has a similar interface):

A Weird and Wonderful Setup

If it weren’t for frequent video conferencing, I wouldn’t have bothered with this weird setup. But now that I have it all put together, it works really, really well. While remote, I can use the in-development API server but still have crystal clear conversations with my team. And it opens up some cool new possibilities too.

Since “How to connect to the VPN for this project” is now an executable script in my project’s repository, the rest of my team can get up and running in no time, without digging through emails to find that one message that included the link to download the Cisco AnyConnect client that only works on Windows.

And since the VPN no longer hijacks my whole network, I can potentially be connected to two or more at the same time, in case I ever need to quickly switch between a couple of projects.