Article summary

User-centered design that ignores the technical landscape is folly. The designs may tell compelling stories and cause stakeholders to pull out their checkbooks. They may make everyone feel like all those dot voting exercises were time well-spent. But without a healthy view of technology to ground them, they’re nothing but fever dreams drawn in the swirling brainstorm vapors still choking the air in your project room.

“But shouldn’t we try to imagine the world as it could be, free from the constraints and mental models of the present? The world changes fast and we’re designing the future!”

Yes, absolutely. Freeing ourselves to push boundaries in order to meet user needs is important. But how long does design need to stay in that constraint-free, Willy Wonka dream phase? At some point, construction needs to start on the dream, and technology should be on your mind.

Technical Knowledge Leads to Better Design

At Atomic, we apply user-centered design to define software that meets users’ needs and can be built, help our customers define a project plan and budget, and then work together to build and deliver the software. While we’re working through design, we know that the development start date is probably weeks or months in the future, rather than years or decades. The software world moves fast, but the reality is that development effectively starts with today’s technology. For some dreams, that provides a real constraint.

Plus, beyond the constraints, awareness of technology during design is a positive force. It can help cover the “boring” needs, allowing more time to be spent on the interesting, compelling features that really make a design unique. Technology provides leverage to make those interesting parts come together quickly and effectively. A cohesive vision that aligns user needs with technical capabilities can also extend the value provided by a design. From this viewpoint, technology offers not just constraints, but accelerant to fuel the design.

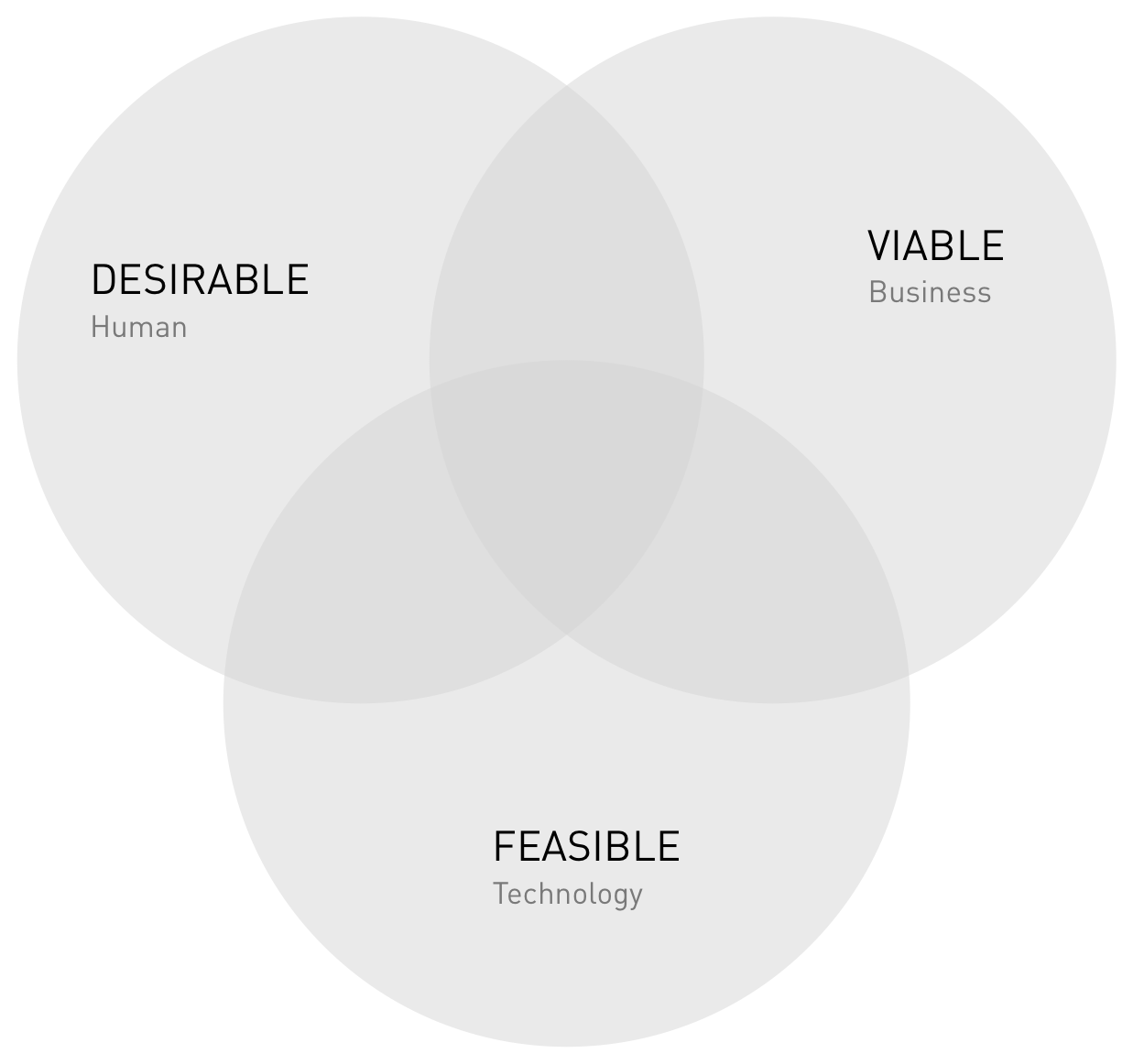

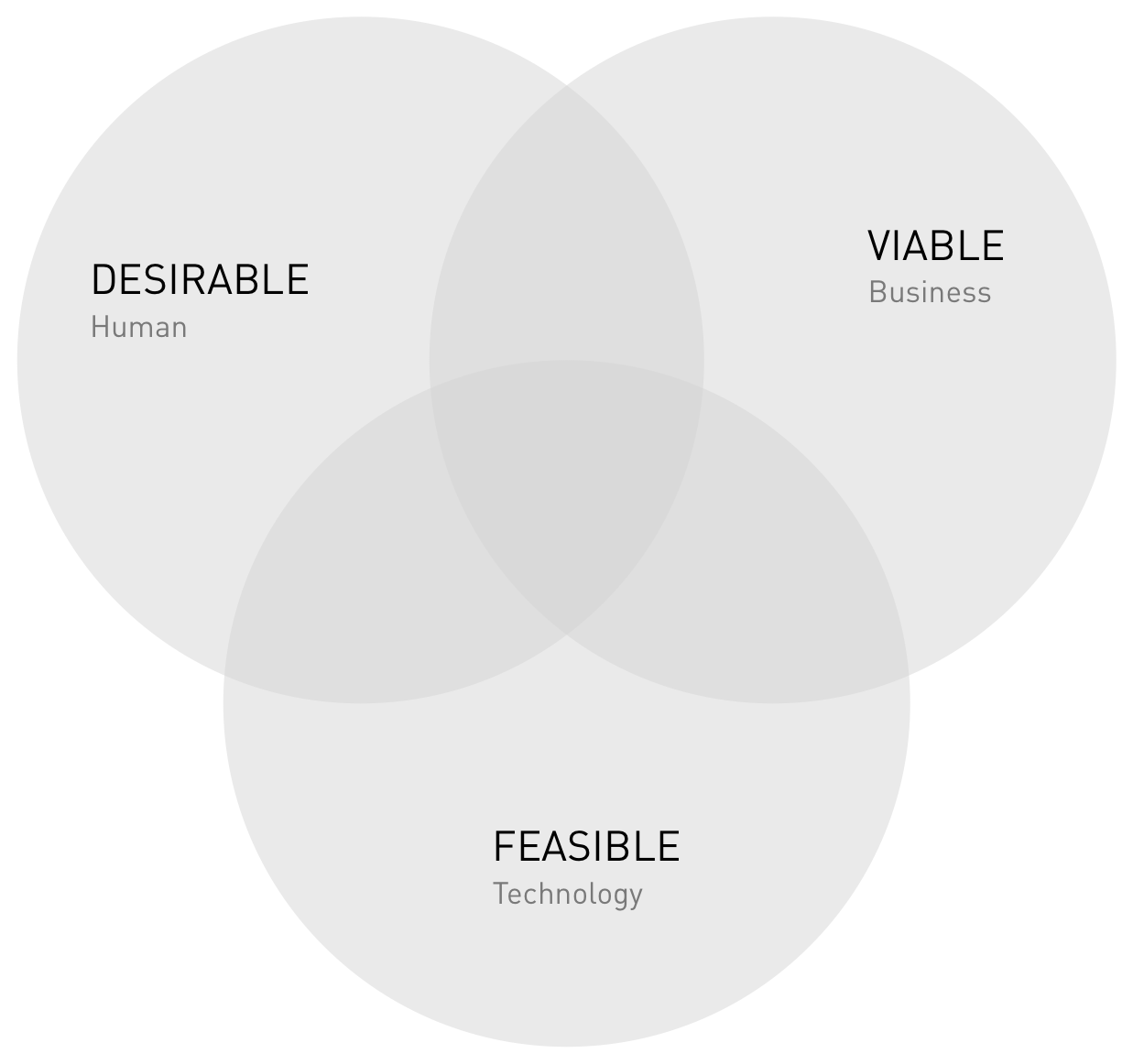

This isn’t new thinking. It is represented in IDEO’s Design Thinking approach where the goal is to create designs that are Desirable (Human), Viable (Business), and Feasible (Technical).

My only complaint about their description of the technical lens is that, at first read, it might sound like constraints are the focus: Does technology make this possible, or not? A broader perspective of the technical lens, which I believe IDEO intends, leads to more interesting questions:

- How can technology make this hard problem feasible to solve?

- How can we better align the design with technology to control construction cost and time?

- How can technology extend the value or desirability of this design?

Atomic’s design expertise, paired with technical insights from nearly 15 years of building software for our clients, has taught us to leverage technology to build value quickly and efficiently and provide extended value to stakeholders and users.

1. Push the boundaries of your technical constraints.

What are the real limiting factors of the technical ecosystem for a design? Not the imagined limits, or boundaries of the team’s current knowledge, but the real, hard, unlikely-to-be-moved limits imposed by technology or imposed on technology?

As with all of these considerations, designing with constraints in mind is a balancing act. Constraining a design with too many artificial boundaries can easily result in an uninspiring experience and mediocre fulfillment of user needs. On the other hand, missing key constraints can result in disappointed stakeholders, software that can’t be built or is too costly to build, or ugly workarounds for users.

If there are constraints hindering the design, push against them a bit. Dig in to find out how hard the limits really are. Do a technical spike. Share information about a human-placed constraint with someone who has the authority to change a decision. Just don’t assume that everything that looks like a wall can’t be moved.

Some of the specific constraints that we pay attention to (and question) during design include:

- Devices used for interaction

- Limits on technology to use (or not use)

- Capabilities of related systems

- Data that doesn’t exist

- Limits of science & computing

2. Identify capabilities that focus or extend a design.

Consider the technical capabilities that exist or could be built. Which ones could be leveraged in the design to make efficient use of time and money and provide extended value to users?

One option that should always be investigated is the opportunity to use existing applications or libraries rather than building something custom. These existing resources typically provide important feature sets at a fraction of the cost of custom software and should be cheaper to maintain in the long run. Evaluating the capabilities of prebuilt systems can also help fill in gaps in a product backbone.

From the custom-built angle, try to identify features that can be applied in more than one area of an application so you can maximize the value of time spent building the features. For example, identify a good feature set for navigation and use it repeatedly. The team will need to keep an eye on the balance between leveraging general features and meeting focused, divergent user needs — nobody will use those powerful, generic features if they can’t make the connection between them and their needs. Good use of pre-built software and re-use of feature sets is critical to delivering a solution that is cost effective today and maintainable for the long term.

Capabilities to look for include:

- Platform-provided interaction patterns and widgets

- Common feature sets across different areas of an application (e.g., navigation, editing tabular data)

- Existing modes of communication

- Features that can be provided by existing software

3. Consider how patterns of users’ needs align with technical concepts.

What are the big-picture ideas behind users’ needs? How do those ideas align with concepts behind various packaged software solutions and design patterns?

Zoom out a few thousand feet from the specific feature level; look for the bigger patterns and general themes. Are there features that show a content management theme? Different users who need access to ask a wide variety of questions about the system’s data (ad-hoc reporting)? Users who need to preserve previous versions of data (versioning)?

Pulling together these big-picture concepts helps identify areas where specific tools and development patterns can help meet users’ needs. Giving them names helps the team talk about them. It can also provide established ontology to support shared understanding of a problem space and help expose opportunities for the system to provide extended value to users and stakeholders. Recognizing and designing for big concepts early has a huge effect on the cost and time needed to build a design.

For example, when I hear:

“Other people make requests of my team. Different people have responsibilities for different parts of a request. The requests are hard for all of us to track, and I don’t have good insight into how well we’re serving our customers.”

I think:

It sounds like we’re talking about Workflow Automation. I know there are tools that support custom workflow definition, handle notifying responsible parties, and provide insight into request status and team metrics. Let’s explore what that typically looks like and see if there is something pre-built that fits the specific needs here.

When I hear:

“We need to know who is making changes in the system and what they’re changing. Sometimes we just don’t have very good visibility into how that number got set. And that number affects these other calculations. It’s just not very transparent.”

I think: Event Sourcing might be a helpful paradigm here. Storing data about each change in addition to the resulting state can help the system provide a view into who is changing what, as well as the cascading impact the changes have. It could also help provide other powerful features like undo/redo.

Conceptual alignment is useful at the feature level, but it goes deeper as well. For example, tools that operate in the workflow automation problem space will reflect differing opinions and assumptions about how workflows should operate. Who’s responsible for a task, an individual or a team? Is the tool focused on the core problem space, or does it aspire to extend into other peripheral areas? Picking a tool or paradigm that conceptually aligns with the system being designed can provide extended value and help the tool fit more cohesively into the design. Essentially, the more the various parts of a system agree about how the world works, the easier it will be to get them to work together.

Some areas to watch for conceptual value include:

- Patterns that repeat across different areas of an application

- External tools that align with application’s conceptual model

- Paradigms that support categories of user needs in addition to good leverage for the future

Technology > Constraints

Technology can provide so much more than constraints to design. It can make solving difficult problems possible, provide leverage to build the most compelling parts of a design more quickly, and help extend the value of a design. Keep these aspects of technology in mind throughout the user-centered design process.