Article summary

I have been noticing a trend lately: when I tell people about my adventures in ham radio, their response is usually along the lines of, people still do that? Ham radio is not dead. It is alive and well, and you should check it out.

I have been noticing a trend lately: when I tell people about my adventures in ham radio, their response is usually along the lines of, people still do that? Ham radio is not dead. It is alive and well, and you should check it out.

Why? Making a long distance international contact using just your equipment and the equipment on the other side of the radio wave is exhilarating. The ability to communicate thousands of miles with no infrastructure between your and your new friend is very freeing. You are no longer tied to the infrastructure of your power company or your internet provider.

History

Beginning in the late 1890’s with Marconi sending wireless signals at greater and greater distances, other experimenters began laying the foundation for amateur radio in the early 1900’s. More and more people began experimenting with spark gap transmitters, sending morse code wirelessly over long distances. Radio experimenters (paired with the sinking of the RMS Titanic) ultimately resulted in the Radio Act of 1912 to limit these experimenters to certain frequencies. And amateur radio — the original maker culture — was born.

Fast forward 100 years to present day, and you will find amateur radio has grown past spark gap transmitters and morse code. Transceivers have grown from spark gap transmitters and receivers into software-defined radio, which uses digital signal processing instead of hardware audio filters. Morse code, or CW, is no longer the only mode of communicating. Voice and various digital modes now fill the airwaves.

Voice Modes

Voice modes are frequent on the airwaves. One of the more popular you may be aware of is frequency modulation, or FM. FM is often used by repeaters spread throughout the local area, which take in a signal and blast it back out at higher power. This allows you to use lower-powered radios and talk across farther distances. FM repeaters are usually good for at most 100 miles of communication due to the way the frequencies propagate through the air.

FM can also used for making satellite contacts. Groups of amateur radio operators such as AMSAT, launch repeaters into space on satellites. The satellite trajectory is tracked and predicted, and the repeaters can be used to communicate much farther than repeaters on land.

Amateur radio repeaters aren’t the only stations in space either, there is a full functioning ham station aboard the International Space Station. It is used not only for contact with schools but also having conversations with other amateurs here on earth. If you have the opportunity to chat with the ISS, make sure you send in for the beautiful QSL card to verify your contact. For more information, check out the ISS Fan Club.

FM isn’t the only voice mode, there is also amplitude modulation, AM, and it’s cousin, single side band, SSB. Single side band is popular for making longer distance voice contacts (due to its smaller bandwidth) and is popular in the HF range of the the spectrum.

Digital Modes

Voice modes are fun, but I personally enjoy the digital modes. They allow me to combine 2 things that I enjoy: computers and radio. The easiest way to get started with digital modes is to use a special USB sound card to hook up the radio to the computer. This allows computer software to control the transmit receive switch, audio input and audio output. With an application like FLDigi, digital signal processing can be used to modulate and demodulate audio signals into binary data.

The advantage of digital modes over voice modes is their narrow bandwidth. Human voices are much more dynamic and take up a wider area of frequency, compared to a tone produced by a computer. This allows for more efficient radio wave propagation compared to voice modes since the RF power is more concentrated. For example, the typical bandwidth of a SSB voice signal is approximately 3kHz. PSK31 uses phase shift keying, which changes the phase of a carrier signal to represent binary bits with a bandwidth of 31.25 Hz, which is almost 100 times smaller than a voice signal.

The baud rate of PSK31 is approximately 32 bits per second, which seems impossible to use compared to today’s internet speeds. However, PSK31 is used to send a stream of characters, nothing more, and equates to approximately 50 words per minute. However there is one flaw with PSK31: no error correction.

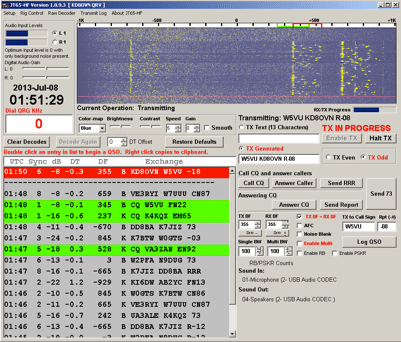

Going to the extreme side of binary modes is JT-65, which includes a large amount of error correction making it very useful for less than ideal conditions. JT-65 is much slower compared to PSK31 and allows for the transmission of approximately 13 characters per minute. At first JT-65 may seem painfully slow, but the time passes quickly, and the minutes it takes to make an exchange allows for tension and excitement to build.

Adding to the error correction is time predictability; transmitters and receivers are synchronized around the minute mark. Transmissions start exactly 1 second after the minute and last exactly 48 seconds. Because of the precision of time required, JT-65 requires your computer to be synchronized within 1 second of the official NIST time at all times.

Getting a License

Amateur radio is the ideal hobby for experimenters, whether you want to build your own equipment, experiment with different modes, or just chat to someone. The good news is, it isn’t hard to get started. I first became interested in amateur radio from a neighbor that lived across the street from me in middle school. I bought a scanner from him and used it to listen, but the requirement for learning morse code to get a ham license scared me away. The morse code requirement has been dropped from the licensing process, making the test much less intimidating.

There are 3 stages of licensing in the US: Technician, General and Extra.

- The technician license is a 35 question-multiple choice written exam and allows for usage of all VHF and UHF amateur bands with limited operations of HF. This is ideal for local communication on FM repeaters.

- The general license builds upon the technicians license and is also a 35-question multiple choice written exam. It allows for all VHF and UHF amateur bands and opens up the HF frequencies for use. It is a large step up in privileges and allows for cross-country and world-wide communications.

- The extra license builds upon the general license and requires a passing grade on a 50-question multiple choice written examination. This opens up all the amateur bands for use and allows you to branch out into the edges of the amateur bands, which are less crowded.

More Information

Ham radio is a limitless hobby and opens up a world of communication. I urge you to learn more, find an exam session, get licensed, and get on the air. I hope to see you on the air soon.

Nice article. I don’t think people today realize how complex, and fragile, cell phones and Internet is compared to the simplicity of point to point communication. I have been a convert to low power QRP and its exciting to see my ‘cell phone’ sized signal go thousands of miles. 73

Low power is exciting, I had a QSO to France a few weeks ago on 20m JT65 at 8W. I will have to turn down the power a bit more so I can have a true QRP contact in my log book! Thanks for the comment John, 73.

Great article, Tony! As John said nobody realizes how truly fragile their cell phone system really is. During the local Nisqually earthquake in 2001 the cell towers were jammed or powered down, landlines simply stopped working and my Amateur Radio Emergency Service (A.R.E.S.) team was the ONLY communication available to our county offices (including the sheriff and fire departments) for almost 3 hours. We were on the air within minutes of the quake and remained on the air supporting the county for almost 3 days.

Any readers interested in finding out more about A.R.E.S. should contact their local Department of Emergency Management or the ARRL at http://www.arrl.org .

Thanks Tom for bringing up the emergency communication aspect of ham radio and for sharing your story about the Nisqually earthquake.

Great article! I’d love to see a link to hamstudy.org added to the other resources you have mentioned at the bottom. I may add a link to here from hamstudy as well, as soon as I figure out the best place to put it…

Thanks Richard. I have been using hamstudy.org to study for my Extra. I included the link in the more information section. I’m looking forward to seeing a link back from hamstudy.org!

Note only as a technical hobby, Ham Radio is relevant to modern technology. Many hams work at places like Motorola, Bell Laboratories, and Defense Contractors. I was one a team leader in a testing group at an aircraft company. The manager was a Ham, and 2 of the 3 “squad leaders” were hams. I was one of them. The third, a female engineer, was not a Ham.

Note, none of our planes got shot down in the Gulf War.

Doug, WB9IDJ.

Hi,

thanks for the nice article. There are a few minor problems with it though. Fldigi specifically does not require a TNC. It uses a sound card interface to bring audio from the radio to the computer and vice versa. A TNC generally has a serial interface and does some amount of processing on the data as well as converting data to sound to be transmitted. ‘Sound card’ is very generic and can mean the use of a sound interface built into your PC, an external USB sound card or a device with serial ports integrated for PTT and CAT control. The important thing is that fldigi (and JT65 software and many others) do not require an external TNC.

Most TNCs are limited to X.25 packet operation for VHF and UHF although there are also modems for HF (PACTOR for example) that are sometimes called TNCs. Generally TNCs are used for packet. My D72, D710 and TS-2000 radios all have built in TNCs. For fldigi I use a Microham USB-3 sound card interface. Signalinks are popular for this purpose but I prefer RS-232 based PTT over VOX so I spent a little more.

The reported range and operation of repeaters is also not quite right. 100 Mile range is very optimistic and not generally achievable, certainly not with an HT at ground level. An HT with yagi antenna on a mountain top aimed at a well positioned repeater may get 100 miles or more but these are border cases. An HT or mobile radio in a car can get a few miles to dozens of miles of range to the repeater, all depending on terrain, antennas, radio etc etc. Repeaters also don’t quite ‘amplify’ signals. They receive on one frequency (input) and re-transmit that signal on another frequency (output). The difference between in and out is called offset and is generally standard depending on the band and frequency.

I hope you don’t mind the corrections and I encourage you to review and challenge them if you feel they are incorrect. That’s one of the other things hams do with a passion: discussions :-)

Over the weekend I hiked up Fremont Peak and Angel Island in California. I used my TH-F6A handheld to have several nice QSOs on repeaters close and far. I experienced exactly what you described, the thrill of talking to someone without requiring infrastructure other than the repeaters maintained by fellow hams.

What is your callsign?

73,

Sander W1SOP

Hi Sander,

Thanks for adding some points of clarification! I have made some revisions.

When I was writing about the repeaters I was thinking of an extreme case. The GM Amateur Radio Club has a repeater with an antenna on top of the Renaissance Center, the tallest building in Detroit at about 700 feet. This height allows for a coverage area that is about 100 miles in diameter for mobile stations. GMARC has a net every Monday at 8pm, I encourage you to join on EchoLink at node number 99846.

73,

Tony KD8OVN

Love it!!! Thanks!

Kathy Austin N8JLJ