Scratch is a block-based programming language/editor created by the MIT Media Lab in 2007 with the goal of teaching kids to code. It is a widely popular tool and has been used by millions of people. It was also my introduction to the world of computer science, and it is a huge reason why I’m working as a software developer today. Let’s look at three Scratch games I made in middle school that went viral due to being featured on Scratch’s homepage and what I learned from making each game.

My Introduction to Scratch

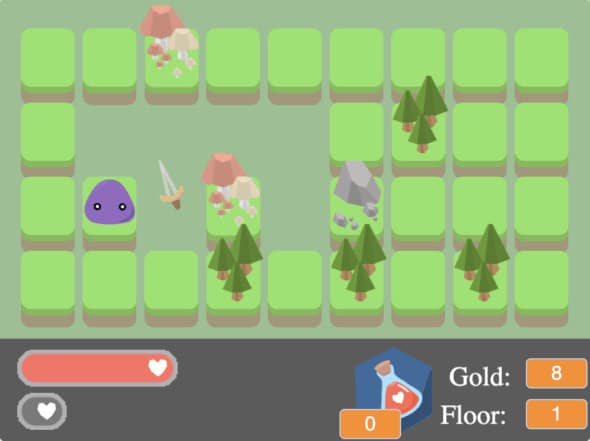

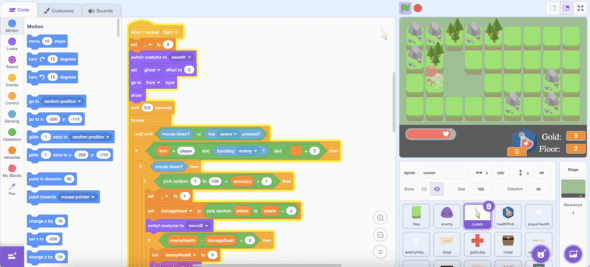

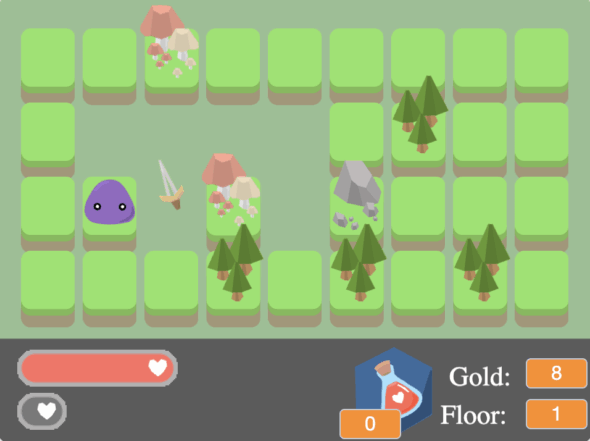

A screenshot of the Scratch editor for my game Fractured Forest

I discovered Scratch through an elementary school summer school program when I was 10 years old, going into fifth grade. Aside from the required English and math classes, students could pick one fun elective class. This summer, they were offering an elective with a title something like: “Making Video Games with Scratch.” My 10-year-old brain saw “Video Games” and immediately signed up.

It didn’t take long to become hooked on Scratch. Something about dragging blocks onto the screen and seeing them affect objects in the game window was mesmerizing. The class provided computers for us to use during the day, but I wanted to delve in deeper. So, I downloaded it onto the family computer at home to spend more time with it.

Every day after class, I would go home, hop on the computer, and spend hours playing around on Scratch. To me, it was just dragging blocks into an editor. But, I was learning how to code, even if I didn’t realize it. Scratch is a complete programming language that includes variables, conditional statements, loops, and more — core concepts I still use in my job as a software developer. I had so much fun taking the class, I signed up for it the next summer, too.

I was using Scratch 1.4, a desktop application (the screenshot above is from Scratch 3.0+). A lot of those 1.4 projects are now lost since I only saved them locally to my family’s computer. But, in 2013, Scratch 2.0 introduced a web-based editor that let users save their projects online and release them for others to play. The projects mentioned in this post are all still playable on the Scratch website today.

Click Farm

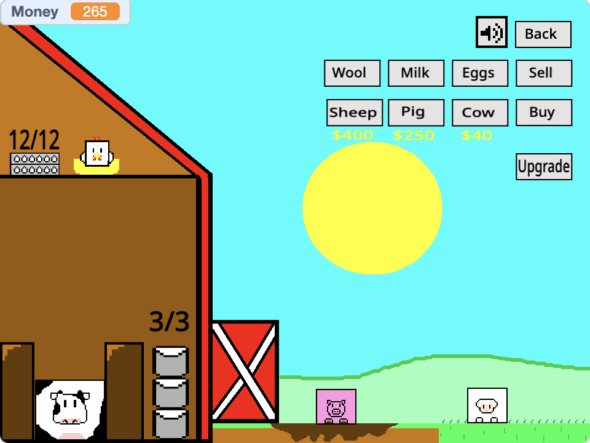

Play the game: https://scratch.mit.edu/projects/14673585/

The first game I made that garnered a lot of attention was called Click Farm. I made it in sixth grade in 2013. The game’s premise was simple: click on animals to get coins, use coins to get more animals, repeat, all while being serenaded by an 8-bit rendition of One Republic’s Counting Stars. (I guess that was my favorite song at the time?) When I finished the game, I hit the publish button and let it sit for a few days. A few days later, I logged onto Scratch and saw that my inbox was flooded with notifications.

Hundreds of people had played it. My game was featured on the front page of the Scratch website and exploded in popularity. As of today, the game has been viewed 88,000+ times.

This project is interesting in that it is the earliest documented example of code that I have written since all my projects from Scratch 1.4 were lost. I see some obviously programming flaws when looking back at the code. For example, there are a lot of if-else statements with empty else conditions, if statements chained together unnecessarily, a loop that runs every frame of the game, which sets the chicken to the same position, etc. But I was still able to use variables and conditional statements to make a functional game. For a project that I made in 6th grade over a weekend, it was a great accomplishment.

Bloop

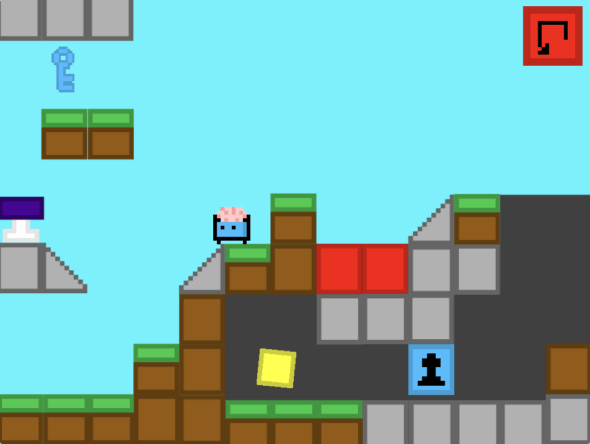

Play the game: https://scratch.mit.edu/projects/24006651/

Still riding on the success of Click Farm, I knew I had to keep making games. My next viral game came one year later in 2014 and was a simple 2D platformer called Bloop. You play as a blue blob with its brain sticking out. (I haveno idea why I went with this character design.). Coding-wise, Click Farm had been a lot simpler to program. Most of the coding logic consisted of game objects waiting to be clicked on and then incrementing the money counter. Bloop was more challenging because it required platforming physics. And with no concept of what a level editor was, I painstakingly hand-placed every tile individually for each level.

One thing that greatly helped me was the fact that all projects on the Scratch website are open source. For any project, you can click a button to see all the code written for it. This was immensely useful when making my platformer, as I could find other platforming games on Scratch, look at the code, and try implementing the code into my own game. Once I had the character moving, jumping, and not falling through the floor due to my ground collision code being broken, I had a lot of fun designing the levels. The game currently has 20,000+ views.

Fractured Forest

Play the game: https://scratch.mit.edu/projects/114609829/

In 2016, my middle school STEM teacher told me about the National STEM Video Game Challenge. It’s a video game development competition for middle school and high school students hosted by the Joan Ganz Cooney Center and E-Line Media. Feeling up to the challenge, I got to work on a turn-based exploration game called Fractured Forest, which has 15,000+ views. The game consists of 20 levels with a randomly generated grid of tiles. The goal is to keep clicking on tiles, trying to find the staircase to the next level. But watch out! Some tiles have enemy slimes on them that get increasingly more powerful as you keep playing. This game was my first time programming randomly generated levels and turn-based combat.

A few months after submitting my game to the challenge, I got an email informing me that my game had been selected as the winner in the middle school Scratch category. My family and I were flown out for the award ceremony at the National Geographic office in Washington, D.C., along with the other winners. I also received a cash prize, and a separate cash prize that went to my middle school’s STEM program. At the ceremony, they had a Q&A panel with professionals from the video game industry. They discussed how the skills we had used to make our winning games could also lead to a career in software. The panel was very eye-opening for me, since I had never considered that my love for programming could be a job.

Scratch: The Start of a Coding Journey

While Fractured Forest was the last game I ever published on Scratch, it wasn’t the end of my coding journey. Four years after publishing the game, I was a freshman at Case Western Reserve University pursuing a Computer Science Degree. Five years after that, I am now a year into my first job post-college as a Software Consultant and Developer at Atomic Object.

Logging into Scratch to write this post, it was cool to see that I am still getting notifications in my Scratch inbox from people commenting on my games, which is crazy to me considering that the last game I published on the site was almost a decade ago. I haven’t finished a game since Fractured Forest, but I have recently started working on a new game that I hope to release one day. Even though I have since moved on to different game engines, Scratch will always hold a special place in my heart as the engine that started me on my coding journey.