Article summary

LangGraph is a powerful framework for orchestrating stateful workflows in LLM applications. Part of designing a robust workflow is having a firm grasp on the foundations of the execution model. I recently ran into some scenarios that challenged my understanding of how tasks are scheduled in my own LangGraph agent.

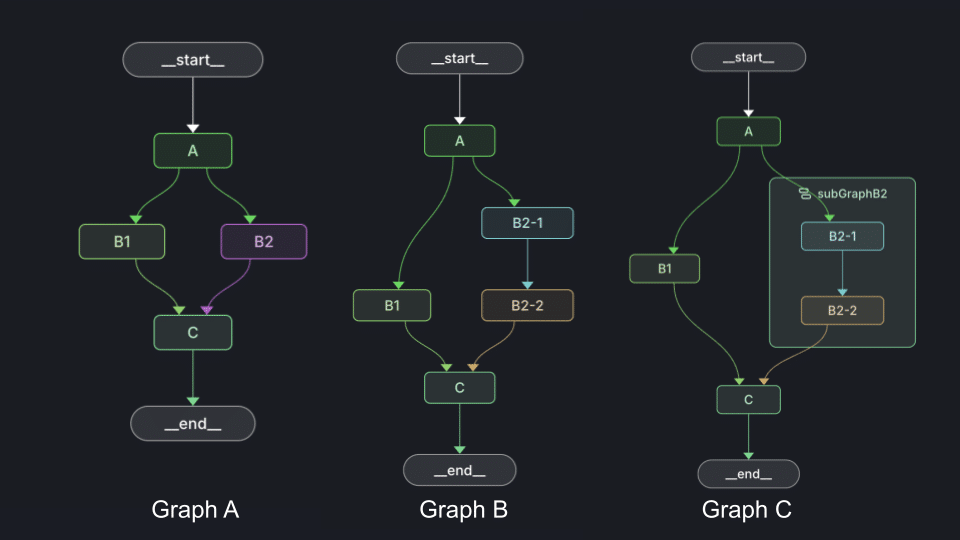

Let’s start with a little brain teaser. Below are three graphs, see if you know how many times node C will execute in each instance. Assume each node is a simple state function with standard single edges. I’ll include the example code at the bottom of this post.

Ready for the answer?

…

…

…

Graph A executes node C once.

Graph B executes node C twice.

And Graph C also executes node C just once.

Is that what you guessed?

Supersteps

The key to understanding LangGraph’s execution model is understanding supersteps. When a graph is first invoked, LangGraph marks the entrypoint node as active and all others as inactive. After all active nodes complete a new superstep begins by activating any nodes that have a state update on an incoming edge. This process continues until all nodes are inactive. I think of this as a sort of “drum beat” that the graph marches to.

Revisiting the Graphs

If we use the knowledge of supersteps to analyze our original graphs, we can see why C behaves slightly different in the three scenarios.

In graph A, node A is the first superstep and nodes B1 and B2 activate in the second superstep. In the last superstep, node C activates. It doesn’t matter that it received messages on two incoming edges, just that they arrived on the same superstep.

In graph B, we introduce an imbalance to the graph’s legs. This makes it so that messages arrive to node C in two different supersteps. That causes node C to execute twice.

The important thing to note in graph C is that each graph keeps track of its own supersteps. So from the perspective of the top level graph, the entire subgraph activates during the second superstep and the next step does not start until the subgraph has completed. The subgraph maintains its own supersteps independent of the main graph.

Join Edges

The LangGraph API gives us back some control with the concept of join edges. If we make a small modification to graph B, by transforming .addEdge("B1", "C").addEdge("B2-2", "C") into .addEdge(["B1", "B2-2"], "C") we get node C executing only once again. Join edges enforce that the execution model waits for messages from both incoming nodes before activating the destination node.

I feel the documentation around this behavior difference is lacking. In my mind those two statements seem interchangeable and the documentation explaining the difference is not easily discoverable.

One pitfall to watch out for with join edges is that if one of the incoming nodes does not finish, the destination node will never execute.

Practical Tips

- If you’re using the fan-out fan-in pattern to parallelize a few quick nodes, be sure the align leg lengths.

- When parallelized nodes don’t have an equal number of steps, consider encapsulating each task in a subgraph.

- Watch out for state merges across subgraphs. A subgraph will output its entire state when it completes.

- Use join edges to explicitly declare scheduling intent.

These fan-out fan-in scenarios are just one small corner of LangGraph’s execution model. These examples helped me grasp the concept of supersteps and I look forward to applying what I’ve learned to more complex patterns.

Appendix: Code Reference

Shared Code

export const GraphState = Annotation.Root({

nodesExecuted: Annotation<string[]>({

reducer: (acc, value) => [...acc, ...value],

default: () => []

})

});

export function basicNode(nodeName: string): () => typeof GraphState.State {

return () => ({

nodesExecuted: [nodeName]

});

}

Graph A

export const graph = new StateGraph(GraphState)

.addNode("A", basicNode("A"))

.addNode("B1", basicNode("B1"))

.addNode("B2", basicNode("B2"))

.addNode("C", basicNode("C"))

.addEdge(START, "A")

.addEdge("A", "B1")

.addEdge("A", "B2")

.addEdge("B1", "C")

.addEdge("B2", "C")

.addEdge("C", END)

.compile();

Graph B

export const graph = new StateGraph(GraphState)

.addNode("A", basicNode("A"))

.addNode("B1", basicNode("B1"))

.addNode("B2-1", basicNode("B2-1"))

.addNode("B2-2", basicNode("B2-2"))

.addNode("C", basicNode("C"))

.addEdge(START, "A")

.addEdge("A", "B1")

.addEdge("A", "B2-1")

.addEdge("B2-1", "B2-2")

.addEdge("B1", "C")

.addEdge("B2-2", "C")

.addEdge("C", END)

.compile();

Graph C

const subGraphB2 = new StateGraph(GraphState)

.addNode("B2-1", basicNode("B2-1"))

.addNode("B2-2", basicNode("B2-2"))

.addEdge(START, "B2-1")

.addEdge("B2-1", "B2-2")

.addEdge("B2-2", END)

.compile();

export const graph = new StateGraph(GraphState)

.addNode("A", basicNode("A"))

.addNode("B1", basicNode("B1"))

.addNode("subGraphB2", subGraphB2)

.addNode("C", basicNode("C"))

.addEdge(START, "A")

.addEdge("A", "B1")

.addEdge("A", "subGraphB2")

.addEdge("B1", "C")

.addEdge("subGraphB2", "C")

.addEdge("C", END)

.compile();