In my last post on content strategy, I talked about some high-level practices for strategizing around website content. I advocated for aligning content with user goals and being merciless toward your content when you prioritize quality over quantity. Successful content is useful to users and entertaining.

Now I’d like to look at some tactical practices that will help you connect with your users, ensuring that your website content is in line with their goals while helping your stakeholders execute their business model.

Identify The Problem Space

So, how does one measure the performance of content? How do we know if we have a content problem? And if there is a problem, how do we determine what that problem is?

As with any undertaking, we form a hypothesis about the performance of content and then test it with data. Data about how users navigate through content is freely available; just set up Google Analytics on a website. This shows you which parts of a site are garnering attention and where users are dropping off in the navigation flow. For a small fee every month, Crazy Egg can give you insight into how users are interacting with your content, using heat maps, scroll maps, and segmented confetti tools to show you which portions of each of your pages are capturing your users’ attention. These are all important pieces of data as we seek to reorganize content around users’ goals.

But as amazing as modern analytics are, they always leave an inquiring mind with questions. Questions? But aren’t analytics cold, hard data? Shouldn’t they be enough to tell us what sort of content is drawing the most attention? Sure, but this is only of secondary importance.

Let me draw on allegory for a second. As in academic historical inquiry, the historical record can usually tell us what happened with some degree of certainty. What is much more difficult and important to understand is why it happened. In this context, imagine you could travel back in time and interview key historical figures personally. The historical record is valuable, but if you want to figure out why certain things happened, first person interviews are more valuable.

That’s what user interviews are like. They give us the chance to investigate why things happened directly with the people who made them happen. Similarly, web analytics offer us a record of when an interaction happened and what occurred. But what they can’t tell us is why that interaction happened. To do that, we need to jump into the fray and get in touch with our users.

So as we examine analytics data, we look for areas of inquiry to include in our user interviews. Remember, these areas of inquiry should help find the intersection of users’ goals and the continuing operation of the website’s business model.

Gather Data Through User Interviews

My colleagues at AO have already written several excellent posts on the methodology of user interviews. I also highly recommend Steve Portigal’s “Interviewing Users” as a handbook on the practice of conducting interviews and gleaning insights from your users’ experiences.

Go Back to Personas

During the early part of any project, we create a set of user archetypes called personas. These personas serve as design tools which we can reference and talk about as we begin constructing a web project. They help personify the user goals we are designing for.

But personas are provisional until they have been evaluated in the light of data. After conducting user interviews and synthesizing design insights, I recommend returning to these provisional personas and adjusting or recreating them as necessary to align with reality.

Set Goals (Know What “Good” Means)

Now we know quite a bit about our users’ goals, and we have identified problem areas in the content. What we need to do next is create a plan for mitigating these problems and to align with our users’ goals.

The first step in creating a plan within the context of content strategy is to determine what “good” content is. How do we know what it should look like? Sure, we want content that helps our users achieve their goals, but what does that mean?

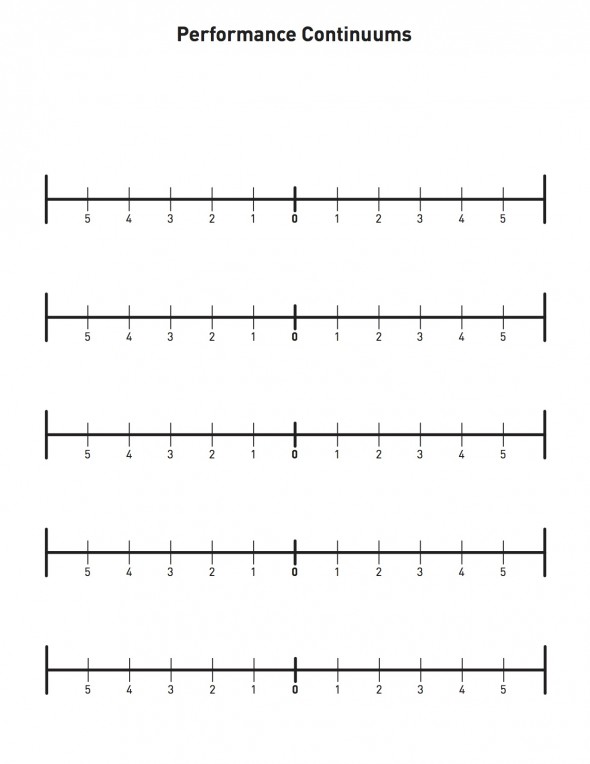

Good is very rarely a matter of black and white or right and wrong. To complicate matters, when you work with various stakeholders, you may encounter a variety of opinions about where to take a certain piece of content. In these instances, I love to use the Performance Continuums tool created by Abby Covert and Dan Klyn. This tool offers a great way to create alignment amongst a group of people about what “good” means in a certain context.

On a recent project, we had a situation that called for Performance Continuums. We had one faction of stakeholders who said, “We need to appeal to a younger audience. We can’t be historical or academic. We need to be more contemporary.” Meanwhile, another group opined, “Being contemporary isn’t faithful to our historical mission or our brand.” Both of these things were true. It seemed like we were at an impasse. But if we decided that “good” is on a continuum somewhere between these two points, we could find a place of agreement, and the tone of content could be contemporary YET historic.

We can also use performance continuums to be a heuristic for the strategic and tactical changes we make to a website’s content structure. To do this, we establish where we want to be on a continuum, and where we think we are currently. Then we can evaluate the effect of changes we make by the direction we move on that continuum. As long as we are moving in the direction we have established, we are “good.”

Another way of measuring content is to evaluate it against SMART Goals. SMART is an acronym that means: specific, measurable, achievable, relevant, and time-bound.

Abby Covert came up with the idea of having stakeholders set goals by filling out a Mad Libs-style worksheet. We gave stakeholders a set of worksheets that were literally fill-in-the-blank questionnaires they could use to set goals for different pieces of content. We encouraged them to think about the heuristic we had just put in place with our performance continuums.

- What sorts of goals could we set that would help us specifically measure our progress with certain demographics?

- What sorts of benchmarks could we set that would help us see that our changes were working?

- What sort of time frame were we thinking in?

The stakeholders loved the exercise and found new excitement for the project as they began to connect emotionally with what their new website would do for their business.

Create An In-and-Out Plan

At this point, we had several good heuristics for judging the content in our possession. It was time to identify our core content.

Core content is the part of your content that rests squarely at the intersection of your users’ goals and your business model’s activity. We have a very simple activity for identifying this content. As designers, we consider the largest buckets of content in our possession. We evaluate these buckets using the heuristics we’ve created previously. We come to agreement on which parts of the site we think are most in line with the goals of the site’s users. Then we put stakeholders to work, asking them to take part in a dot vote on which parts of these buckets are most important to the function of the business. The content buckets that have the most cross-over are our core content.

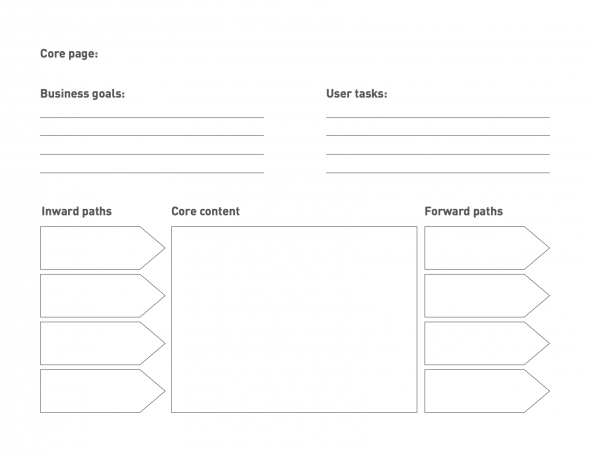

Once this core content is identified, we can use core models to guide users strategically through the site. I got this idea from Are Halland’s presentation at the IA Summit in 2007. He advocates organizing a website’s content around the core tasks a user comes to the site to accomplish. The end goal is to create forward paths through your content so users can go from one useful page to the next, all while trying to meet their own goals and helping your business model run.

We used Halland’s idea of core models during a recent kickoff workshop to gather data from key stakeholders and content generators for a large news and commentary website. After we had identified the core content on their website, we handed out worksheets which identified the page-type or template in question and had the stakeholders think about how that page served their business model and helped their user base achieve their goals. We then planned inbound paths to those areas of the site, as well as outbound paths to other parts of the site in accordance to what would be most useful to users. Finally, we spent time sketching what we thought these pages should look like, along with key calls-to-action for outbound paths.

Conclusion

In 2010, erstwhile Google CEO Eric Schmidt said that every 2 days we create as much information as we did up to 2003. Content is exploding at an exponential rate. As designers in the midst of this information flood, we must be able to create useful, lightweight heuristics that will work to wrangle large pools of content. We then need to be able to use these heuristics to create a plan for our content that will lead both users and business to a fruitful end. Otherwise, all this content is just noise in the digital landscape.